Joan C. Durrance

Research, Teaching, and Service

Professor Durrance's wide-ranging research and teaching interests included the study of social and cognitive aspects of how individuals seek, give, and use information in different contexts; community information systems; the evaluation of information services; and the professional practice of librarians.

Click here for vita.

1970s and 1980s

In the mid 1970s Professor Durrance studied at the University of Wisconsin, focusing on community engagement and briefly was on the faculty of the University of Toledo Community Information Specialist program. These experiences led to her pursuing a PhD at the University of Michigan. Her groundbreaking dissertation research in the late 1970s identified the difficulties that citizen activists encountered in obtaining government and local information needed to help solve community problems. That research resulted in her first book, Armed for Action, in 1984 and various journal articles. Importantly, it shaped her research, teaching, publication, and service activities throughout career.

In the 1980s Professor Durrance’s research and teaching at the University of Michigan focused both on information services in libraries, particularly the reference interview, on the difficulties that citizens encountered in obtaining community information, and the gaps between those two bodies of research. During this period and throughout her academic career, her community service included working with various professional organizations to develop more effective approaches to providing community information resources and meeting community information needs.

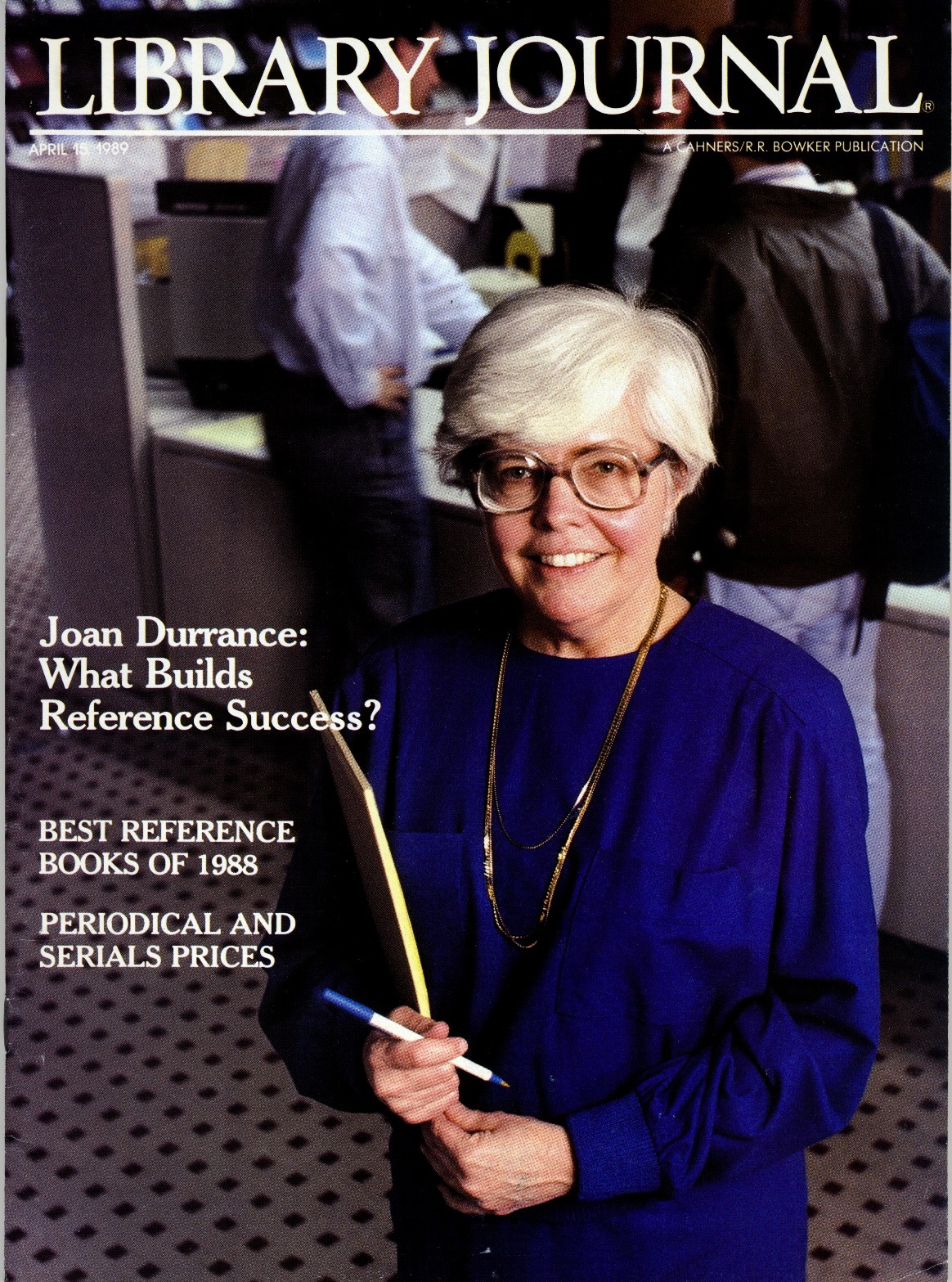

During the 1980s Prof Durrance engaged students in the professional practice class in her Willingness to Return Study. Students observed and interacted with librarians and tested communication factors associated with successful reference interactions. The results were published in several journals, including the field’s most prominent, Library Journal. A decade later the American Library Association presented her with its R.R. Bowker-Isadore Mudge Award for “distinguished contributions to reference librarianship.”

In the late 1980s Durrance was chosen by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF) to analyze approaches used by librarians and other professionals who participated in a major WKKF project—Education & Job Information Centers-EJICs. This experiment was designed to help community agencies, including libraries, to devise strategies to assist people whose jobs had disappeared due to technological or social changes combined with a major economic recession. Experimental job centers were set up in multiple towns and cities in five states. She observed and analyzed at multiple sites around the country. Prof Durrance and others associated with this major project identified both the needs that job seekers brought to the centers and the strategies that were developed to meet those needs. Following this research she wrote two books and several journal articles focusing on this project. This Kellogg-funded project also contributed to the development of job & career centers in public libraries across the nation that built on the Kellogg-funded models.

1990s

In the late 1980s and into the early 1990s Professor Durrance’s research, writing, and teaching focused increasingly on anticipating information needs and evaluating the effectiveness of community information service models. Her research resulted in a group of journal articles and two books: Serving Job Seekers and Career Changers (1993) and Meeting Community Needs through Job and Career Centers (1994).

In each decade of her career, Professor Durrance involved UM masters and doctoral students in cutting-edge research focusing on community involvement and change in professional practice. In the 1990s as the World Wide Web became available, she and her students in her classes worked with citizens and governmental agencies to add critical local content to the Internet. In addition, she actively pursued funding opportunities that would contribute to relevant community focused information provision, enhance professional practice, and increase the effectiveness of evaluation models.

By the middle of this decade it became possible—for the first time—for organizations and individuals to use the Internet to create content, post it, and interact with others.

Leaders at the W. K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF), concerned that—without significant changes—libraries as institutional information sources and librarians as information professionals might be left behind in the emerging information age. Under the leadership of Dean Daniel E. Atkins, the Kellogg Foundation awarded UMSI an unprecedented multi-million dollar grant. The WKKF chose the School of Information to develop models for creating approaches that would assure that libraries and library and information science educators could effectively exploit the Internet and emerge as viable partners with other Internet players. The School’s project was called the Coalition on Reinventing Information Science, Technology and Library Education CRISTAL-ED.

In 1994, early in the life of that major Kellogg initiative at the University of Michigan, Professor Durrance sought and obtained funding to develop the Community Networking Initiative (CNI), a multi-faceted community-focused Internet project. The overall aim of her CNI project was to apply emerging Internet capabilities to local community initiatives, increase the quality of emerging networked community information, and, importantly, identify and disseminate community networking best practices. CNI funding allowed her to identify cutting-edge community networks, conduct site visits at four best practice sites, and analyze factors that contributed to community networking viability. During that year, she and other community network pioneers formed a national association to foster the development of community networks. With a team of UMSI graduate students developed the Community Connector—a model for community and local government Internet content.

One of the most important CNI projects was The Flint Community Networking Initiative, collaboratively developed with the Flint Public Library—a library that served a community with high levels of unemployment and poverty and other key players in Flint. The Flint CNI started in 1995 by creating one of the first public library Internet linked computer labs in the nation. After the remodeling a library space for computers and Internet connectivity (no small task in those days since there were, literally, no models to follow), UM students and project staff then trained a cadre of Flint librarians to use the Internet (training was designed and conducted just a few months after the first Internet browser was available and, again, was no small task). These librarians learned how to contribute content about the community to the new World Wide Web. The librarians who received that early Internet training, in turn, shared their knowledge with other librarians and the general public. Flint Public Library staff developed an extensive program to provide Flint teenagers with the skills they needed to work with community organizations and provide these Flint community groups with their first Internet presence. At the end of that project several Flint teens presented their work to the Board of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

The Community Networking Initiative in the mid-1990s influenced librarians and local government agencies in many communities to work together to provide networked community information. A video made by the Library of Michigan less than 5 years after the project began shows how quickly the adoption of this concept had spread in one state (video courtesy of Charles Severance). Several national conferences developed by community network leaders encouraged the development and strengthening of community networking models throughout the country.

In the latter part of the decade the University of Michigan CRISTAL-ED Kellogg grant as well as grants by the Foundation to four other LIS programs designed to reinvent LIS education were culminating. There was evidence that several field-leading LIS programs with Kellogg and other funding were making major changes in LIS education models with assistance from these grants.

In 1997 Prof. Durrance as President of the Association of Library and Information Science Education (ALISE), focused its annual conference, ALISE’97 Reinventing the Information Profession, on LIS educational reform. She obtained funds from the Kellogg Foundation to enhance the conference and invited representatives from the Kellogg Foundation who attended and addressed the conference on the need for education renewal in LIS.

Also in 1997 Prof. Durrance approached the Kellogg Foundation suggesting not only that an analysis of the changes in education to the programs funded by the Foundation was needed, but, importantly, a field wide examination was necessary to determine if other LIS programs were keeping up or seriously falling behind—i.e., unable to adequately educate library and information science professionals for a new century. The Kellogg Foundation willingly provided a grant to ALISE to conduct such a study. Prof Durrance and a small group of educators designed a research project that became the most extensive examination of the field of library and information science (LIS) in over 70 years.

The project, known as the Kellogg-ALISE Library Information Professions and Education Renewal Project (KALIPER), was conducted by a team of twenty scholars from thirteen programs in the US, Canada, and England and advised by a blue ribbon panel of LIS educators. The KALIPER study conducted between 1998 and 2000 documented major changes in LIS education then being undertaken in the U.S and Canada. The KALIPER study found a “vibrant, dynamic, changing field” that was “undertaking an array of initiatives.” The summary was published in 2000.

Building on the KALIPER study, Professor Durrance in 2004 examined in retrospect the major changes in LIS education brought on by the information revolution and the convergence of multiple disciplines.

In 1998, Prof. Durrance, working with Post-Doctoral Researcher and later University of Washington faculty member Karen E. Pettigrew, received a major federal grant from the Institute for Libraries and Museums (IMLS)—Help-Seeking in an Electronic World. This research, which was conducted through a national study of community information provision and series of site visits, examined ways that best practice libraries provided digital access including: how they engaged in civic partnerships, identified needs expressed by citizens, and developed relevant service models. They disseminated their findings in various ways, including conference presentations, journal articles including the lead (cover) article in Library Journal in 2000, and a book published in 2002: Online Community Information: Creating a Nexus at Your Library.

By the end of the decade, the field of community informatics—an interdisciplinary field that focuses on using community information and information technology to help empower people in communities, specifically focusing on social, cultural and economic development—was emerging. Community informatics provided an umbrella for scholars from different fields to apply their skills for the benefit of communities. Prof Durrance and her former doctoral student, Kate Williams contributed the community informatics article to the LIS field’s encyclopedia.

In 1999 using the collaborative approaches fostered by community informatics, Prof Durrance and Prof. Paul Resnick, building on earlier research by both of them obtained funding from the Kellogg Foundation to explore ways that computer based after school programs could contribute to social capital. The project sought to help teenage residents of underserved communities develop information, communication, and technology skills that would allow them both to create resources and become resources in their neighborhoods. Data were collected from teen focused after school programs in five different agencies in three states.

2000s and 2010s

In the early years of the new century, Prof. Durrance and her co-principal investigator (PI), Prof. Karen Fisher, received two major federal grants from the Institute for Museum and Library Services-How Libraries and Librarians Help in 2000 and Understanding Community Information Use in 2002. These studies involved dozens of case studies of both information behavior and best practices of libraries and other community information providers. Findings appear in journal articles and are summarized in the following reports: How Libraries and Librarians Help: Context-Centered Methods for Evaluating Public Library Efforts at Bridging the Digital Divide and Building Community and Approaches for Understanding Community Information Use: A Framework for Identifying and Applying Knowledge of Information Behavior in Public Libraries.

Prof Durrance’s work in this decade built on and expanded her earlier research, teaching and service focusing primarily on people’s information behavior and use and the ability of information professionals to anticipate citizen information needs. She and her research partners also engaged in ground-breaking work that resulted in providing professionals with approaches and tools to identify and measure user/client-centered outcomes of services rather than the traditional measurements used by librarians that focused only on counting users, items circulated, program attendance, etc. UM SI masters and doctoral students were heavily involved with this work. Likewise, Professor Durrance actively engaged with other researchers through the Association for Library and Information Science Education (ALISE) and the Association for Information Science & Technology (ASIST) and with professionals through a variety of community and information related groups within the American Library Association (ALA) to disseminate the outcomes model.

Because the findings of her outcome focused and information needs research were central to developing community-centered professional practice, Durrance, her co-PIs, doctoral students and masters students, used a variety of approaches to disseminate their findings. It was crucial that scholars, students, and, importantly, information professionals—who were in a position to make changes in practice—learn about this research. Approaches included workshops, presentations to professionals, speaking at conferences, and of course, publication. SI students enrolled in Prof. Durrance’s Outcome Assessment class were instrumental in creating some of the first case studies showing successful use of outcomes in agencies that they had worked with. Several of these were included in the well-received 2005 book on outcome assessment: How Libraries and Librarians Help.

Professor Durrance’s work was recognized during this decade in a variety of ways. She received the University of North Carolina School of Library and Information Science Distinguished Alumna Award in 2002. In 2004 she was named the University of Michigan School of Information Margaret Mann Collegiate Professor of Information. In addition she was selected as Chicago Public Library’s Scholar in Residence in 2004. In 2005 she received the ALISE Award for Professional Contributions to Library and Information Science Education. That year she and her co-author received the Jesse Shera Award from the American Library Association.

At her retirement party in 2010 the School prepared and showed a whimsical PowerPoint tribute to Professor Durrance’s professional contributions and personal life.